Published on 14 September 2020

Lees dit artikel in het Nederlands.

The debate in parliament about the Nordic Model earlier this month was the most recent attack on sex workers' rights in the Netherlands. In a year that included the proposal of a new law, and the problems many of us experienced due to Covid-19, it is easy to lose track of the current state of sex workers' rights in the Netherlands. Hence this overview.

Panic and solidarity

Without any warning, we lost our jobs. Covid-19 hit hard and suddenly, and for the first time in Dutch history, sex work became prohibited. Barbers, massage therapists, and other 'contact professions' were allowed to start working again on the 11th of May, but the government insisted that sex workers had to stay home until at least September.

Almost all sex workers were barred from receiving corona support, and many colleagues did not know what to do. Half a year without any income: How will I pay my rent? Where do I get the money for groceries? What will be left of my business?

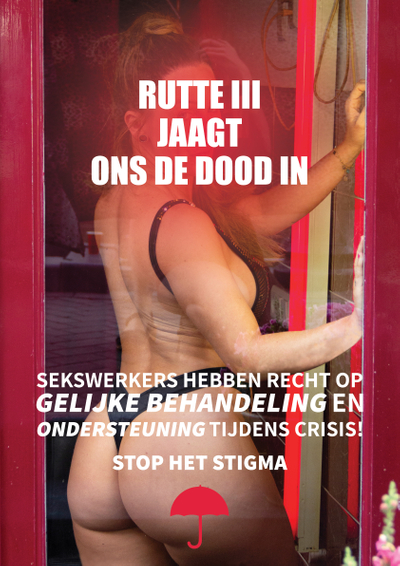

The fact that we were allowed to start working again on the first of July was thanks to several initiatives from sex workers, who continuously kept pointing out how unsustainable this situation was. Posters were distributed, there were press releases, and a press conference.

Solidarity among colleagues took care of some of the groceries. An emergency fund was set up, as well as a helpline and, where possible, sex workers loaned each other money.

But that help did not reach everyone. More than a few colleagues could not make ends meet, resulting in evictions and empty bellies. Some of us saw no choice but to go to work anyway, which posed not only health risks, but also the risk of heavy fines and a criminal record. For undocumented colleagues there was also the danger of deportation. Clients with bad intentions knew that working was prohibited, and that sex workers were therefore less likely to report violence.

New law

Covid-19 was by no means the first blow to sex workers in the Netherlands in recent times. In December last year, the bill for the Sex Work Regulation Act (WRS) was published. It was a horrible proposal, and hundreds of people informed the Secretary of State why this proposal would mean a further weakening of the position of sex workers.

Despite this feedback, the proposal was sent to the Council of State (Raad van State) virtually unchanged and is expected to be discussed in Parliament this autumn.

Should the law be passed, all sex workers (including those working in a brothel or through an escort agency) will need their own permit. To get it, you must be 21 or older, be allowed to work in the Netherlands, and convince an official that you are 'self-reliant enough'. In all other cases you will not receive a permit, and will have to risk working without one.

Unlicensed workers will be fined 20.750 euros when caught. The same applies to collaborating with or offering a service to unlicensed sex workers. In some cases there is even a prison sentence of up to two years. It will therefore be more difficult and more dangerous for us to hire an accountant, driver, or assistant, for example. Customers of unlicensed sex workers are also punishable under the WRS.

All licensed sex workers, anyone caught working without license, and anyone who does not pass the licensing process, will be entered into a national register, which is cause for concern for many colleagues. Due to the stigma still attached to our profession, a registration as a sex worker is not without risk. There is no guarantee that this information will not have a negative effect on, for example, a visa application or the allocation of a home in the future.

Many colleagues therefore doubt whether they would apply for a permit at all under the WRS. Especially because this permit alone is not enough to work independently. Because, in that case, in addition to being a sex worker, you are also a sex business by law. And for the latter you will still need a separate permit issued by your municipality.

The fact that this all took place against the background of the corona crisis made it difficult to organise resistance. Meeting was (and is) only possible under strict conditions, and many colleagues were (and are) too busy surviving to put time and energy into the WRS.

Nordic Model

And then there was the debate in parliament. As a result of a citizens' initiative, the representatives debated whether paying for sex should become illegal. This 'Nordic Model' is popular with conservative Christian groups that would prefer to see sex work disappear completely. Under the guise of 'safety' and 'helping vulnerable women', they argue for a form of criminalisation that is detrimental to the safety and job satisfaction of sex workers.

For example, research by Amnesty International shows that, once clients became criminalised, sex workers in Norway are taking more risks to protect their clients from the police. They meet in remote places and have to make do with less personal information on which to base a security check.

Whether you like your job or not, you are always better off when your workplace is safe and there is access to solid help when you need it.

And in Sweden, after 20 years under this model, sex workers there still seem to have to work under unsafe, less pleasant conditions. Last week in parliament the false distinction between 'voluntary' and 'involuntary' sex work was made again, but job satisfaction should not play a role in whether you deserve labor rights. Whether you like your job or not, you are always better off when your workplace is safe and there is access to solid help when you need it.

It was Green Left's Niels van den Berge who put the finger on the sore spot with the words: “When it comes to wrongdoings, we have to be consistent. Are we also going to ban [picking] peppers and asparagus? Or is it about sex work being a completely different sector to you? Then say that, because then we can have that debate.” In a striking twist (GL voted in favour of the predecessor of the WRS in 2016) Van de Berge advocated decriminalisation of sex work.

Although decriminalisation will not happen any time soon, the Secretary of State promised to investigate various forms of sex work policy, including the New Zealand model of decriminalisation. Incidentally, such a study has already been done, with one of the most important conclusions being that sex workers should be listened to.

This debate seems like a prelude to the discussion that will undoubtedly erupt as soon as the WRS is sent to Parliament. We must not allow this discussion to be hijacked by parties that have moral objections to our work. They will try to misuse our stories for their own agendas, thereby making our work less safe.

Standing strong together

It is important to stand together. To fight for our rights or the lean on one another. In the Netherlands there are a lot of (co) sex worker led initiatives such as SAVE, Liberty, TransUnited, PROUD, Sekswerkexpertise and the Prostitutie Informatie Centrum you can join or go to for information. There are also social work organizations like Door2Door, Seksworks, Spot 46, Belle or P&G292 who often organize activities or sounding board groups. And let's not forget about what the sex worker community does best: taking care of each other in times of need.

*Images are from the poster initiative.